Side note: I added a new short story to my website. You can check them all out here!

One of my favorite museums in the world is the famous Museum d'Orsay in Paris. In addition to the magnificent collection that is always on display, the museum also holds on-going special exhibitions which gather together exquisite pieces that the museum normally does not display and are arranged by a certain theme.

When Albert and I visited the museum over a year ago, they had a Manet / Degas exhibition. Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas were well-known frienemies in the art world, and both were and still are considered some of the best painters of their time. The exhibition put many of their works side-by-side so that you could see how these two rivals' works were so different yet equally striking.

I'd never been interested in Degas because I thought he was just obsessed with ballerinas and couldn't really see the point in that, and I disliked Manet after learning through Ocean's Eleven (of all things) that he was a bit of a pervert. Well, the exhibition further confirmed that Manet was a sex addict (he ultimately died of syphilis). Not only that but I grew a strong distaste for his work as well.

He felt very much like a 19th-century social influencer who used connections and, in particular, spectacle to get as many views as possible. All his paintings felt very trendy and ephemeral, kind of like fast fashion. To be sure, his works showed an extremely keen eye for what would catch people's attention as well as an enormous amount of art history knowledge, which he used to create scandalous paintings that went against conventional expectations. There was also an impressive amount of flair and personal style that only masters of their craft can use. But maybe it was because his art felt like it was gunning for views or because it seemed so steeped only in the here and now that I just couldn't savor his work. It was like a piece of meat that was cooked wonderfully, but there just wasn't any marrow to suck on.

I approached Degas with an equally uninterested attitude. He felt kind of like a pervert too, what with all his paintings of young ballerina girls lifting their legs and prancing about in tights and tutus. But as I made my way through the exhibition and especially as I saw his work side-by-side with Manet's, I couldn't help but fall in love with Degas' paintings.

First of all, he drew way more than ballerinas. He still did give off the feel of a pervert in some senses, but it wasn't so much because he chose young women as his subjects (he also chose fully-clothed men regularly). It was because of the perspective his paintings always took. If Manet felt like an in-your-face-give-me-your-likes-super-popular Instagramer, Degas felt like that weird but harmless nerd in the back of the class who would always snap photos of people for his own pleasure without them knowing. (Jonathan from season 1 of Stranger Things comes to mind.) It was like he was a shy, silent, and socially-really-awkward guy who liked to watch people instead of actually going up to them and talking to them. But that didn't mean he didn't like them or find them deeply interesting.

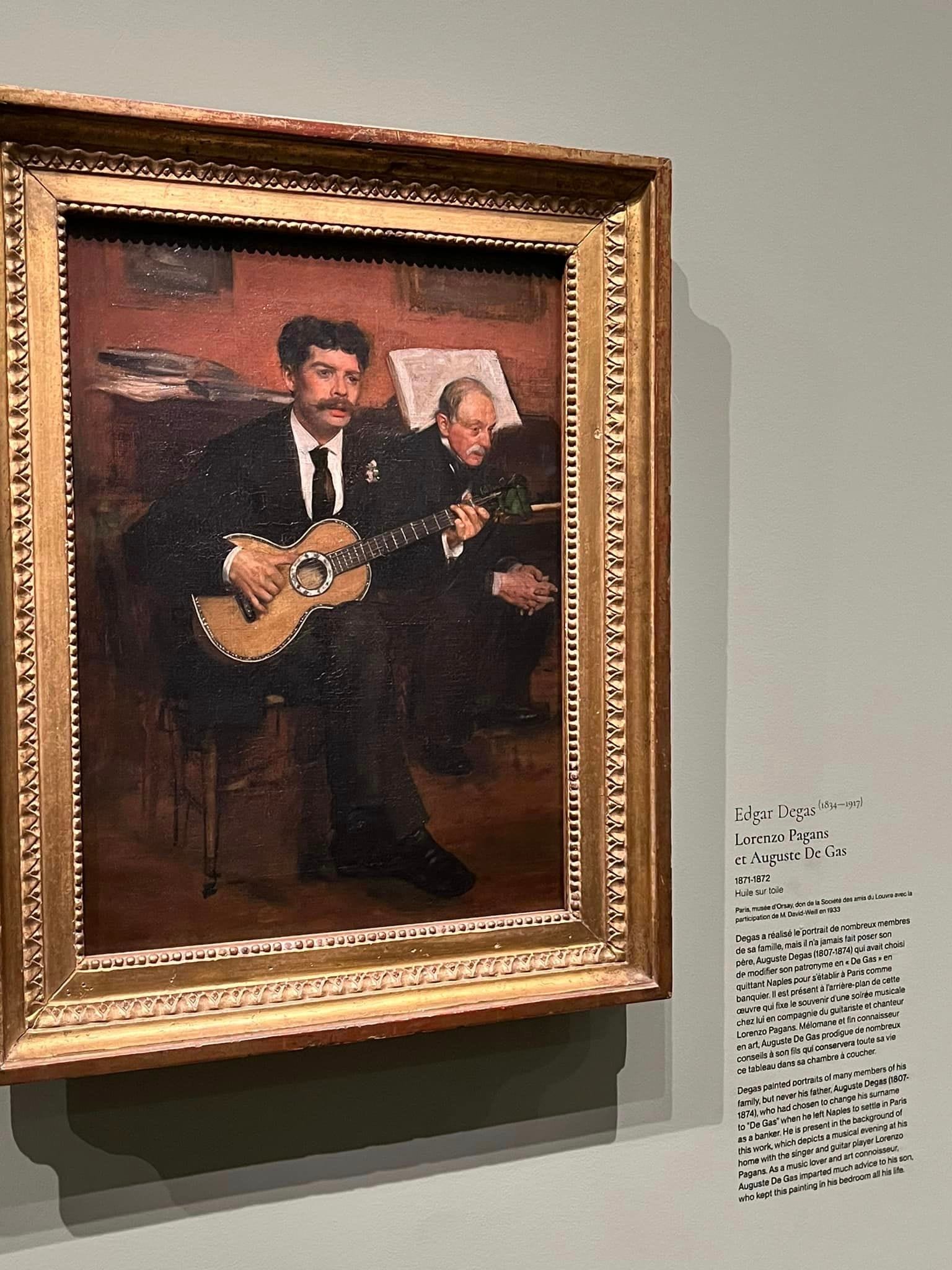

His painting of the guitarist Lorenzo Pagans (which is the featured photo for today's blog post), in particular, glued my feet to the floor and had me staring for ages. What immediately caught my attention was the insane amount of detail that went into the guitar. My photo didn't capture it, but the white detailing on the guitar is meant to be mother of pearl. He painted the sheen of the mother of pearl so accurately that I had to check again and again that he hadn't simply cut some real pieces of the white gem and pasted them onto the painting.

The guitarist's expression also held my gaze. Degas captured so perfectly that far-off look of a musician casually strumming away, that distant gaze of someone who is both here and not here. The way he captured the flow and movement of the guitarist's body made me see how the musician was, perhaps, twitching his foot along to a soft beat, or swaying back and forth to the melody, or repositioning himself from time to time to adjust his arms and legs as he cleared his throat. I could imagine how everyone in the room would appreciate the music, even if it was just casual practice, and how everyone would nod and wait silently for more if he paused in his playing.

Degas' father in the background added to the atmosphere. I could see him nodding his head now and then, also lost in the gentle music and the calmness of the room. He was an old man, bending with age, thinking in that vague way that's particular to grandparents. Perhaps he would scoot back further onto the bench, clap softly once or twice and continue nodding.

It's a normal scene. Nothing spectacular is happening. It's not a giant picture of a prostitute lying on a bed and staring at the audience, like in Manet's famous Olympia painting. It's a quiet, cozy evening with loved ones and a special guest, nothing more. But maybe it's because so many intricate details were so expertly explored and wielded that this image of a normal evening looked so spectacular to me. Each detail Degas lovingly painted helped this still, inanimate image move and breathe, and this somehow made me feel that such normal scenes in everyday life were also made up of hundreds of precious and well-placed details. It made the normal feel so special, so singular, so meaningful. And perhaps the normalcy of what was occurring was one of the things that made such moments so beautiful. It was beautiful, too, that Degas would memorialize such a moment. He recognized that normal moments in life were scintillating in their own quiet way.

I walked away from that painting changed. Long after we came back from Paris, I continued to savor the experience of having been a part of that peaceful evening from so long ago. I couldn't shake the fact that despite how humdrum the subject of the painting had been, it had absolutely dazzled me. And I had to accept once again, but perhaps more deeply and with less resistance, that the normal is good. The normal is beautiful. The normal is worthy.

You see, I've been a perfectionist and over-achiever my whole life, so saying that "normal is good" can feel downright blasphemous at times. It started out as "hate-studying" because I was so fed-up with all the drama happening in my family, and I believed as a young person that studying my way into a good school and getting a good job would help me climb out of the dark pit that my father's mid-life crises had thrown me into. I saw brilliance and success as my only lifelines of survival. And somewhere along the way, as I continued to do much and achieve much, I became petrified of becoming a normal person.

I felt that I was less of a person if I ever failed, even slightly, at anything and that I would be a worthless human being if I didn't one day become a great woman of great notoriety, if I wasn't "special." The fact that I'd also gone through many traumatic events throughout adulthood, from sexual harassment in the workplace that made me quit my job to a romantic relationship that was both physically and psychologically abusive, added to my need to be someone of some kind of spectacular significance. After all, what was the purpose in everything I'd suffered through if it didn't amount to anything in the end ... if I didn't amount to anything in the end? Did I go through so many years of fear and loneliness and literal hunger just so I could end up as some plain Mary Jane? All that work to survive, all those trials, was it all just so I could die a smelly old cat lady, trapped and alone in a sagging armchair?

I'd struggled over the years to try and put these existential crisis-like thoughts out of my mind. As a Christian, I know that God loves me just the way I am. He sees me as precious because I'm a human being He created, not because I achieved something great with my life. I am precious whether or not I'm "special" by society's standards because I'm special by God's standards. But every time I would try to live my life in a way that was okay with simply being normal and happy, the old existential crisis would kick in and warn me that I was wasting the one life that I had, that I was wasting opportunities to make something of myself, that after having gone through so much in life, I'd simply go to the grave a loser.

But something about staring at Degas' paintings changed me so that I was finally able, in a quiet and gradual way, to embrace normality and see it for what it is: beautiful. I questioned myself for the thousandth time why I couldn't just accept my life for what it was. Why couldn't I just do things that made me happy here and now instead of gunning for a loud and proud future that was as spectacularized as Manet's paintings, a future that might not even come and probably wouldn't make me happy if it did? If I couldn't accept and enjoy the small, normal moments of my life and the small, normal parts of myself, would fame and fortune really bring any significance to my life?

I'd asked myself these questions even before going to Paris, and over the years I had answered myself over and over again that no, it wouldn't bring significance because I knew intellectually and spiritually that it wouldn't. But it was only after seeing that Degas exhibit that the truth slowly started to sink in deeper and in a way that wasn't so difficult or painful to accept. It didn't so much feel like I was losing something by accepting the truth, just that I was making a better decision. It was still difficult putting the truth into practice, to be sure, but from that moment on, I had more drive to pursue the beauty of normalcy and more conviction that the path I was pursuing was the right path. Slowly but surely, I tried harder to make decisions with my life that would make me happy whether or not it came with an assurance of praise and glory.

And eventually, that led me to let go of my ambition of becoming a traditionally published writer and to simply self-publish the novel I've been working on for years.

For the few of you who have had an insider's look at my novel and talked to me about it, this news might come as a surprise. After all, I was so bent on becoming traditionally published and felt like the world would collapse if my debut novel failed to kickstart a professional career in writing. I had big dreams for this book. I could already see myself getting a six-figure advance, easily being offered a contract for the sequel, accumulating thousands of followers on Instagram, and all in all, being set for life.

Part of the reason I had such ambitious goals was because I know that my book is worth a lot. To put it bluntly, I wrote a damn good book that I know is deeper and better written than most books within my genre. I don't even feel like I'm being arrogant by saying this because I know it's the truth. I know the value of my book, which is the greatest thing I've written to date, and I believe in my work 100%.

But as months passed and the novel came closer to its final form and the time to submit my manuscript to professional agents drew nearer, I couldn't push away the fact that I felt a giant boulder of dread pressing down on me every time I thought of the next steps ahead of me. At first, I wondered if I was simply afraid of entering the new and treacherous territory that is the world of publishing. Or maybe it was because I was lazy and didn't want to do the hard work.

But deep down I knew it wasn't fear or laziness that was feeding my dread. The truth was that I knew that I wouldn't be happy if I pursued traditional publishing.

I couldn't bring myself to accept this truth buried within me, though. What was the point of pouring hours and hours of blood, sweat, and tears into this book if I wasn't even going to release it professionally, mass produce and distribute it to every corner of the earth, and make a boatload of money that would prove the value of my work to anyone who would ever lay eyes on it? Why wouldn't I be happy with all the success this book could bring me?

I stayed in denial even as I started submitting short stories to literary journals. I wanted to practice submitting my works to professional journals before I started submitting my most important piece, my book, to agents and big editors. The world of literary journals, after all, is a smaller branch of publishing that would give me a taste of what the bigger, traditional industry is like.

I started submitting Spring of last year, and I learned a lot. And most of what I learned left a bad taste in my mouth. For one thing, I saw that so many literary journals are run only by one ethnicity. There are some drops of color here and there, but the types of stories that are favored really lean toward the tastes of only a few types of people, and an Asian American woman like me is definitely not automatically included in that group of people.

On the socio-political spectrum, too, there is an overwhelming amount of minds that are staunchly biased toward the privileged left. (And no, that's not me trying to rag on anyone who identifies as left-wing. I don't judge people by whatever their political beliefs may be but by how they treat others.) As I continued researching journals and submitting, I grew increasingly alarmed that there are only one or two types of mindsets that are readily accepted and supported by the literary world and that a variety of opinions, even ones that I personally disagree with, aren't given a fair chance to see the light of day, so much so that I feel like authors conform their works to match publishers' expectations in order to have a chance at publication.

Isn't art supposed to be the honest baring of one's soul? And aren't all souls different? Isn't literature supposed to broaden and challenge our minds with different and opposing perspectives? Why is everything so damn uniform? And it's not just in the world of literary journals. If anything, it's worse in the larger world of traditional publishing.

And the way traditional publishing just runs through artists and their literature! The short attention span of modern audiences combine with the industry's greed for profit to create a culture of mass production and valuing popularity over quality. To be fair, there is an over-saturation of terrible literature that editors have to swim through, which means that it's doubly harder for great works to be found, and authors really can be awful, entitled piece-of-crap people too. I'm sure there are plenty of agents and editors out there who try their best to give everyone worth their salt a fair chance.

But I can't help but feel that the publishing professionals who really run things at the top (and even many at the bottom) just mow through authors and their precious works like they're ground chicken meat zipping by on conveyor belts headed for McDonald's. There are so few professionals who treat authors' works with real dignity and professionalism. Art is constantly being minimized into a marketable good rather than being upheld as an exploration of the human soul.

Even as my short stories were accepted and sold to different magazines, I increasingly felt like the works, which I put my soul into, were just a dime a dozen and that the whole act of publishing these pieces of my soul was ridiculously transactional. I hated the fact that I was putting out so much of myself to people who really were just trying to use me for popularity or money, people who were not interested in the preservation of diversity in thought or ethnicity but those who were interested in forwarding only one type of agenda or mindset. There is so little space for originality or honesty in literature, which is supposed to be a medium for both!

But even with all my growing disgust, I kept telling myself that it was what I had to do to be successful, to be special, to be worth something, to prove to the world that this book, which means so much to me, is actually good and not just a worthless child that only a mother could love. That, by extension, I, this book's creator, wasn't just a worthless human being left broken and insignificant by trials and suffering.

It didn't matter that I felt stressed and pressured all the time, to the point of getting into arguments with my husband, at the mere thought of traditional publishing and all the expectations and conformation that would come with it. Because even if I didn't hold so many ideological differences with the publishing world, going professional would mean being held accountable to a whole new set of standards and rules that would forever dictate my process of creating. I was already an insufferable perfectionist who had panic attacks from self-imposed standards. What would become of me when I went professional? Plus, from marketing to collaborating to traveling, there were so many steps in traditional publishing that I simply hated even thinking about, never mind doing. In short, both the job description and the employer sounded absolutely awful. But it was still my dream job, wasn't it? I had to do it.

But then it gradually dawned on me that actually, I don't have to do anything. In fact, if the reason I don't want to do something isn't due to laziness or fear but a real dislike, I shouldn't do it. The only thing egging me forward to go through with something I already hated so much was simply my inability to be okay with being normal, to be okay with being acknowledged only by a few friends and family, to be okay with doing something for the intrinsic value of enjoying the doing of the thing and not for an explosive result. I had to accept that being "normal" is actually not so bad and that happiness and satisfaction won't be found in a glittering future if the plain ol' here and now can't be enjoyed.

The fact that I even wrote a book is special enough, is good enough. The fact that I wrote a good book is even better. Maybe I won't get a million people to buy it if I self-publish. Most likely, I'll be lucky to sell even a dozen. But it's still okay because worth isn't found only in pomp and circumstance. It's found in the small details of life too, the quiet moments, the unrecognized things that often slip past us like silk against skin.

A peaceful evening of listening to the strumming of a guitar is beautiful. Escaping an abusive relationship then using my creativity to write a book that helped me to process the whole mess is beautiful. Self-publishing my precious book because I don't want to pressure myself to do things I don't want to do is beautiful. Having a few friends and family who support my book is beautiful. Dying an old lady, comfortable in my own home, after a living a life that I deem as beautiful is beautiful.

Quantity and grandeur really have nothing to do with how special something is or how much I'm worth. If dazzling success comes, then that's great. I won't complain if I receive a lot of compliments or make money off of my own hard work. But I can honestly say now that if the book doesn't blow up into the next Harry Potter, that's great too. If I write one book after another, go through one phase of life after another, and simply remain a normal person, I'm good with that. As Degas well knew, all that glitters is not gold. What's valuable is the ability to live a life that I'm genuinely happy with and to savor all the small and beautiful details that, despite the lack of grandeur, are infinitely worthy.